What is the scope of the “fashion” design? Fashion was a revolutionary device for hacking the world where people viewed people as symbols and signs when they could not choose how to dress or live on their own will. Now that everyone has a choice of clothes and a way of life, what can we hack into this era?

Fashion to create “new human beings”

Since some time ago, I have had a vague desire to know the origin of textures; textures that human beings feel from things such as art, literature, and fashion. Is it possible to express the essence of our cognitive sense in some universal form? Why does the strong presence of the texture from some objects affect me? It was about 10 years ago that I was thinking these kinds of things all over. At that time, while I studied the relationship between the chaos of chemical reactions and the phenomena of life, I was hoping to analyze human cognition by a rigorous mathematical approach※1.

However, even after reading books on psychology, statistics, cognitive science, and analytic philosophy, I could never be satisfied with the approach written on there. Looking at a math book, I also thought that if I had 100 or even tens of thousands of years, I might be able to get a clear picture of my questions through brand-new mathematics※2. On the other hand, even if I finally figure out something, there is a critical question of whether you want to explain it to someone after all.

How should I live? A vague question arises as to “what ‘I’ is.” The Bible and the Buddhist scriptures, Abhidharma※3 give us a glimpse of how humans have long confronted this metaphysical question. Throughout history, the question of “What is ‘I’?” has gradually transformed into the question of “What is a human being?” But in the end, It comes back to the 1st question: “What am I?”

Looking back at the past while thinking about my own future, I realize that the initial primitive questions of “How should I live?” or “What am I?” that I had been thinking about since I was little changed to the abstract question of “What is a human being?” as I grew older and acquired knowledge. Knowledge gradually induced me to become obsessed with universal subjects such as “human being.” How can we return to the real concrete question, while observing the abstract concept “human being”? This question is different from the original one※4.

As I researched “myself” and “human being” one step at a time, I gradually began to wonder whether it is possible to create or design “myself,” “human being” and its modality and dynamics. From that perspective, in the world, things affect people, people affect things and the environment, and new phenomena and facts are dynamically created as a series of consequence. Therefore, now I see fashion itself, which creates things around people and gradually changes the world, has attractive non-trivial potential as an act we call, fashion design※5.

A man whom I met on a rainy day almost 10 years ago. He has a unique style that draws our attention. What can we learn about him from his appearance?

A man whom I met on a rainy day almost 10 years ago. He has a unique style that draws our attention. What can we learn about him from his appearance?

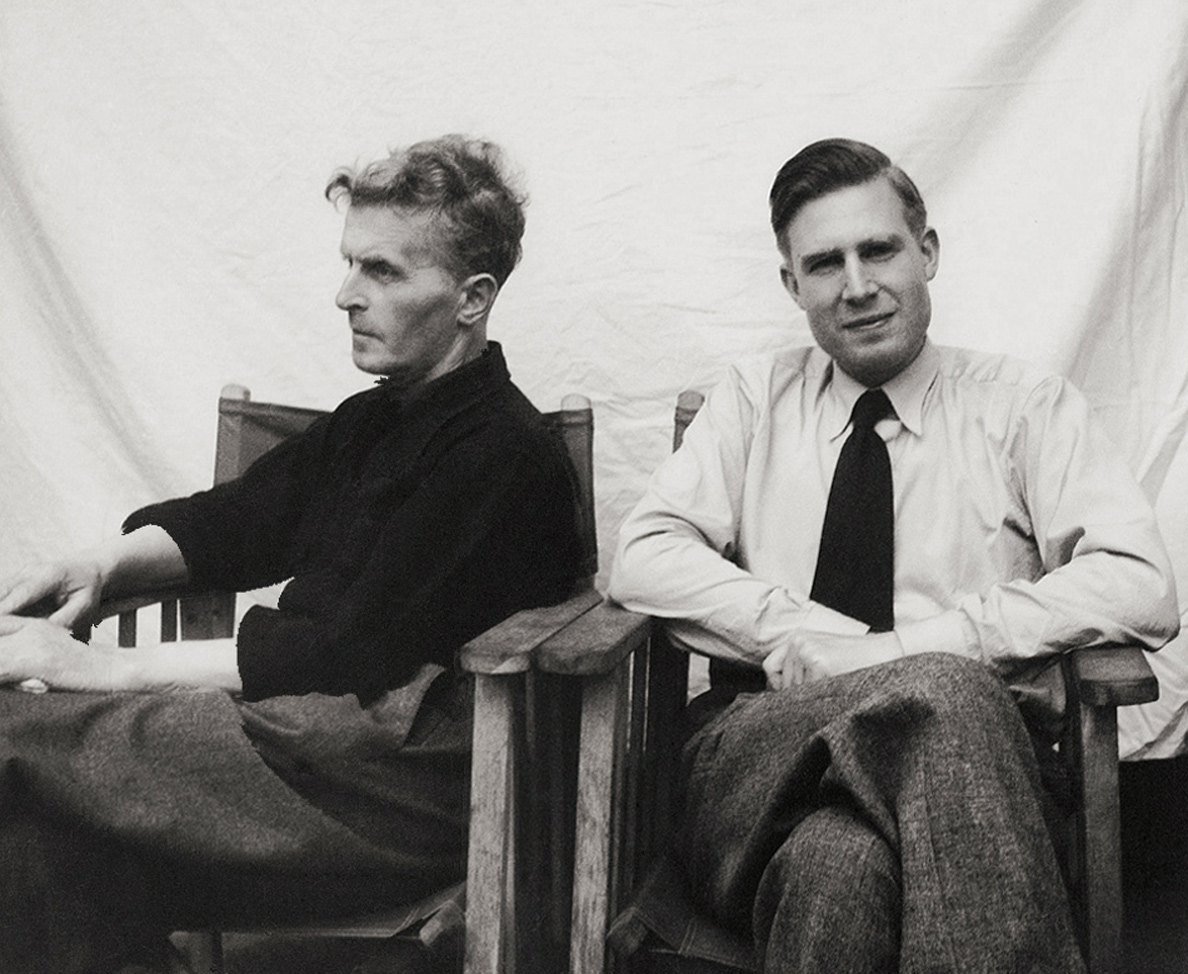

Photo of Ludwig Wittgenstein whom I shared in the footnote. In this photo for example, can we see a system or a component that represents who he is?

Photo of Ludwig Wittgenstein whom I shared in the footnote. In this photo for example, can we see a system or a component that represents who he is?

Designing nearby, designing in-distance

Architect Arata Isozaki※6 sometimes discusses the term “architecture” in his lectures. He mentions that while “architecture” is perceived as almost synonymous with “to build a building” and “to design a building,” in reality, the term covers a wider scope from creating a structure inside a city, creating a city itself, and even to the extent of influencing the dynamics of the people who live in those city, and to creating this dynamics itself. However, the Japanese translation of this term, kennchiku (建築), does not convey this inherent rich meaning of “architecture.”

Some of you may be reminded of the parable of the three stonecutters, made famous by Peter Drucker. A traveller approached the stonecutters, asking them what they were doing. The first one replied, “I am making a living,” the second said, “I am doing the best job in the entire country,” and the third one said, “I am building a cathedral.” According to Drucker, the third man is a great example of a person who understands “true management.” To begin with, the question “what is it that I’m creating?” is a fundamental question for any form of “creation.”

Also, Shusaku Arakawa※7, whom I met in my early twenties pop into my head. Arakawa, who went back and forth between an artist and an architect, often mentioned “To change society, human ethics which is the key element of society, must be changed. To do so, one must first change the human body.” He found potential in architecture as “a machine that could change the human body” and continued to create his works.

It is clear that his scope of work did not cover mere “building” within a scene, but even to the extent of transitioning of human dynamics. He claimed to be a “codenologist,” an enigmatic pseudonym presumably made up as a result of aspiring to design beyond architecture or art-piece; the meta-physical.

We can physically engage with objects or systems. Certainly, we can also debate the structure, the texture, the beauty, the convenience, and the feeling that we get out of these artifacts. However, I cannot help but think about a realm beyond the physical creation, the “happening” that the creator must have wished to happen. People create new dynamics as a result of being influenced by interacting with the physical and also gives influence to others. This could result in a chain of influence; the birth of one single object or system has the potential to change the substance of a larger scale. We are constantly in a mutual relationship with the world. Essentially, isn’t “designing things” should be considered at this magnitude?

For the sake of argument, if we can call a form and a structure of design as “designing nearby,” then we can call a design that covers a wider scope as “designing in-distance.”

Reversible Destiny Lofts Mitaka (三鷹天命反転住宅 Mitaka Tenmei Hanten Jyutaku, In Memory of Helen Keller). A residence, built by the concept of “a residence for not dying.” Built to act from the human body to the mind, an example of an “design in-distance” that aimed to design beyond mere buildings in the scenery.

Reversible Destiny Lofts Mitaka (三鷹天命反転住宅 Mitaka Tenmei Hanten Jyutaku, In Memory of Helen Keller). A residence, built by the concept of “a residence for not dying.” Built to act from the human body to the mind, an example of an “design in-distance” that aimed to design beyond mere buildings in the scenery.

From mode, to code

Just like the term “design,” the term “fashion” is also heavily used every day without a concrete definition. However, I strongly believe that fashion is one area that enables “designing in-distance.” The word “mode※8” that is often used as something similar to fashion derives from “modality.” This implies that the word “fashion” not only suggests “clothes” or “style” but also suggest a dynamic pattern of modality or phenomena in human society. If I were to translate fashion as yousou (様装※9), this could slightly convey a broader picture even in Japanese.

Looking back to the early 19th century, the combination of clothes created a rigorous rule that was used to semi-mechanically sort out social class and communities that people were based in. Because individual’s clothes, possessions, and daily behaviors were limited to their attributes at that time, it was easy to assume their social background from a mere “surface,” their appearance.

We can assume that human behaviors and outfits could be easily associated with an unspoken rule, similar to a law, by looking into the behaviors of those individuals who were in a privileged class, or those in religious orders, or the clergy. Human outfits were “uniforms” for each community and was a way to visualize “institutions.”

This is an illustration of a scene within the Palace of Versailles. Fashion and outfit in the 17th century suggest the social class of each individual.

This is an illustration of a scene within the Palace of Versailles. Fashion and outfit in the 17th century suggest the social class of each individual.

With the times, the rules of apparel turned from institutional rules to the form of “codes.” This code was not like a legal document, but it was more of a courtesy and custom, something that was dynamically generated through tacit atmosphere or interrelation between individuals.

As the static social class starts to collapse, this code also becomes more dynamic. This change let the outfit and behavior of individuals become more diverse and the boundaries of their belonging communities also become obscure. An “individual,” by wearing clothes could possess various faces based on time and locations, becoming “dividual.” (divided, in-contrast to “individual”) And thus, style which was originally a mere combination of objects has changed social dynamics, gradually implementing the “designing in-distance.”

Fashion, religion, and virus

Cristóbal Balenciaga, the successful fashion designer of the 20th century left the following words.

A couturier must be an architect for design, a sculptor for shape, a painter for color, a musician for harmony, and a philosopher for temperance.

Within the century of his appearance, it is said that the manner of clothing based on the human body has ran out. Various styles were born, institutionalized as a uniform, and have been immobilized as the next new category, such as Punk, Trad, Work, Street, Avantgarde, and etc.

Photo of London in the 1980s. An educated computer program could easily profile the social class or attributes of these photo subjects. Likewise, we are unconsciously determining the attributes of the other. The lineage of fashion is about creating a new community by generating a gap between this determination and reality.

Photo of London in the 1980s. An educated computer program could easily profile the social class or attributes of these photo subjects. Likewise, we are unconsciously determining the attributes of the other. The lineage of fashion is about creating a new community by generating a gap between this determination and reality.

Most of today’s creation, except for a slight difference in the detail and texture, are inevitably retrieved in the existing categories. This circumstance can be seen explicitly in the way magazines and media, boutiques, department stores, online stores categorize merchandise.

To simplify this point of view, consider a plane coordinate system, where the immobilized existing categories are placed on the x-axis, and the merchandise and retail prices are placed on the y-axis. The act of designing can be considered as creating an item that can be plotted on this plane, and to plot and land in an unknown realm is considered to be what we know as creating a new style※10.

The turning point of fashion in a cultural context was marked whenever a new type of style was disseminated. The new fashion has hacked the unspoken codes and traditional values and obscured the boundaries of the community. And by evoking sympathy, fashion has changed the status quo.

A new style turns into a uniform of these people who comes and goes along the blurred boundaries. The image of this style spreads amongst the people and affects the mind of the other along with the words associated with this image.

Tadao Umesao※11, a Japanese cultural anthropologist, once advocated the virus theory of religion. But if we consider the viral aspect of fashion, we can see that fashion is a social phenomenon that has religious characteristics. In this sense, Judaism, Islam, Christians, Buddhism have always been influencing the human dynamics; this can be considered as the “designing in-distance” at the ultimate degree※12.

Enabling “The Fashion System” with big data and AI

How can we analyze this design scope of fashion that keeps changing?

Roland Barthes can be an example of those who have analyzed fashion. His approach was based on linguistics, being influenced by Nikolai Trubetzkoi and Ferdinand de Saussure, who argued that fashion had linguistical characteristics. The Fashion System published in 1967 is the compilation of his study. However, the content is far from complete when we see it in today’s standards. Back in the days of his time when freedom was guaranteed, and the human behavior was diverse, human dynamics were far beyond the cognitive limitation.

To avoid theoretical fatal failure, he limited his study subject to fashion that appeared only in magazines. While this analysis itself is suggestive, it was just narrated around the scope of “designing nearby.”

He mentioned on this point as follows.

I have limited myself to the written descriptions because of two reasons, methodology, and sociology. First, the reason for methodology: Mode indeed brings into play several systems of expression: The matter, the photography, the languages. And I couldn’t make a further rigorous analysis of a very mixed material subject. I couldn’t analyze in precision, if I switched from images to written descriptions, and from these descriptions to observations that I could have made myself on the streets. Given that the semiological approach consists of cutting an object into elements and distributing these elements in formal general classes, there was an advantage in choosing a material as pure and homogeneous as possible.

Dialogue between Cécile Derange; France Forum, 5th June 1967※13.

Although his analysis was not sufficient, it may have functioned well 300 years ago. The measurement of the correlation between language and limited human behavior and lifestyle must have been simple.

A common Japanese household of the 1950s. What can we interpret from this photo? Could we drastically change the behavior of the man on the left by tweaking something inside this photo? This is an example of the goal of “designing in-distance.”

A common Japanese household of the 1950s. What can we interpret from this photo? Could we drastically change the behavior of the man on the left by tweaking something inside this photo? This is an example of the goal of “designing in-distance.”

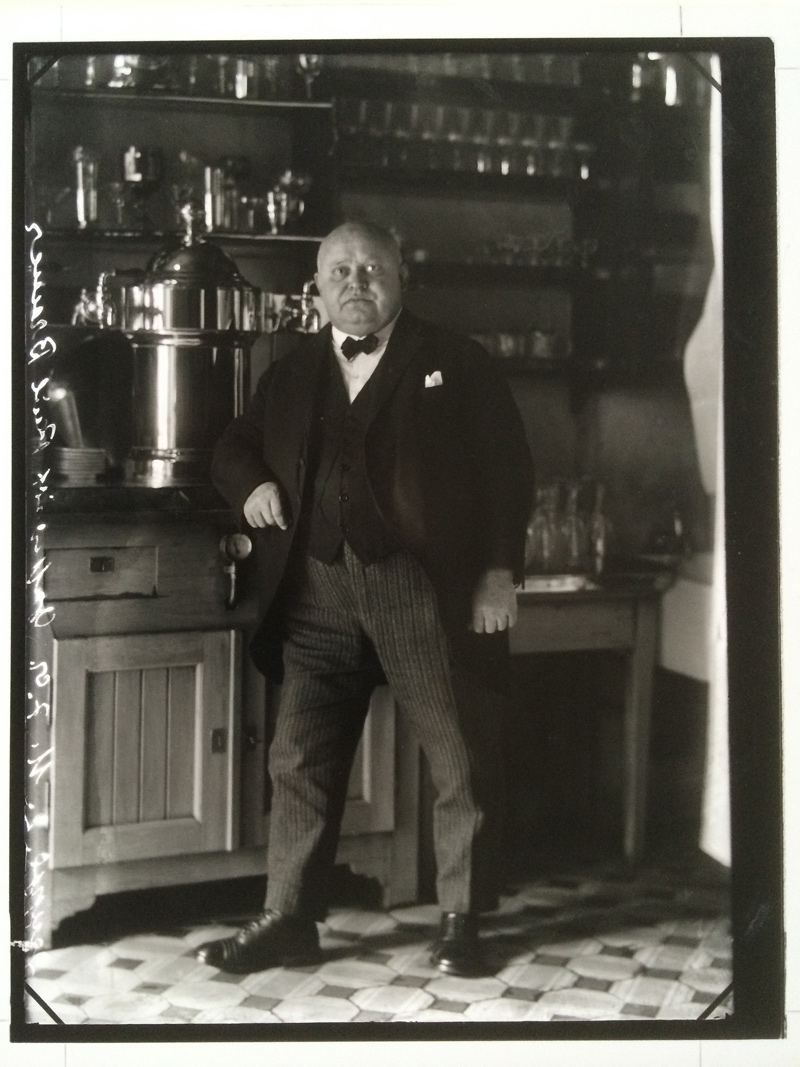

Photo from August Sander People of the 20th Century. Sander shot images of people of various jobs in the early 20th century in Germany. What is the job of this man in this photo?

Photo from August Sander People of the 20th Century. Sander shot images of people of various jobs in the early 20th century in Germany. What is the job of this man in this photo?

Currently, we do not rigorously judge others by limited information such as their state or outfits like in the past. We now become more “dividualized.” The low visibility of the world caused by the excessive information that overwhelms the human cognitive limitation accelerated the discrete segmentation and semiotic fragmentation of the world by computers.

Before long, we may end up recognizing the machine filtered world as it was the world itself. If we start profiling human entities by using machine-learned artificial intelligence to mathematically evaluate individuals by variables such as physical characteristics, demographics, activities on social media, then perhaps the world may become very similar to what it was like 300 years ago※14.

Resisting the world of discretion

Fashion design by AI is already in development※15. The discrete mesh that dissects reality will become narrower and the resolution of social visibility will be higher. Under such technological progress, the semiotic analysis (or categorization/classification) that was sought by Barthes, which was originally limited to the analysis of magazine, may be able to cover a larger scope. Then the real nature of social modality and The Fashion System at its full capacity will emerge when the scope of analysis is extended to all textual data, images, or even to all the objects that are connected to the internet.

Now, with the capability of analyzing vast amount of data sets, exploring the depth of human society through the superficial exterior, the approach seen in Barthes’ The Fashion System has become meaningful again※16.

At some point, we may waver between hope and despair within the space illustrated by computers. We will be resisting the new symbolism, in a world that holds the risk of uniforming the world through a new type of filtering and classification.

A space that portrays reality through discretion; things that lose its’ brilliance, that can only be seen by “I/me” or the self. When I recall these, the words written in 1Q84 by Haruki Murakami comes to mind.

If you can’t understand it without an explanation, you can’t understand it with an explanation.

1Q84 BOOK 2 by Haruki Murakami

The strong “I/ me” has always been the one who moved the world that lost its’ mobility, by resisting the uniformization and symbolization. It is the ungraspable modality of “I/ me”, something that is ultimately definite and yet cannot be systematized. The time has come; the time that requires an invention of a new fashion, that hacks the process of the discretion of the world that can further generate a new way of living. The possibility of a new fashion design always emerges from “designing the in-distance.”