Taisuke Karasawa:

Today, I would like to talk once again with Mr. Toshiaki Ishikura—who deeply contemplates the nature of humans and non-humans with a focus on mythological research—about his current research and connections to topics such as art. I believe the first time I heard Mr. Ishikura was at the public research-seminar, “Kashokusei no Jinruigaku*1 (The Anthropology of Edibility)”, held at the Institut pour la Science Sauvage (Institute for Wild Science) at Meiji University. At that lecture, Mr. Ishikura gave a fascinating talk regarding people and food and used the term “Gaizou (external organs)”. Could you please provide a brief explanation of this concept of “external organs”?

Toshiaki Ishikura:

The first time I talked about the term “external organs” was, as you pointed out, in the final research seminar, “Homo Edens: Kashokusei no Jinruigaku (The Anthropology of Edibility)”. Two empirical roots bring us to this statement. One of these roots is the experience gained from the twelve journeys I took with photographer Masaru Tatsuki across the Japanese archipelago, after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, over about one year.

§

Karasawa:

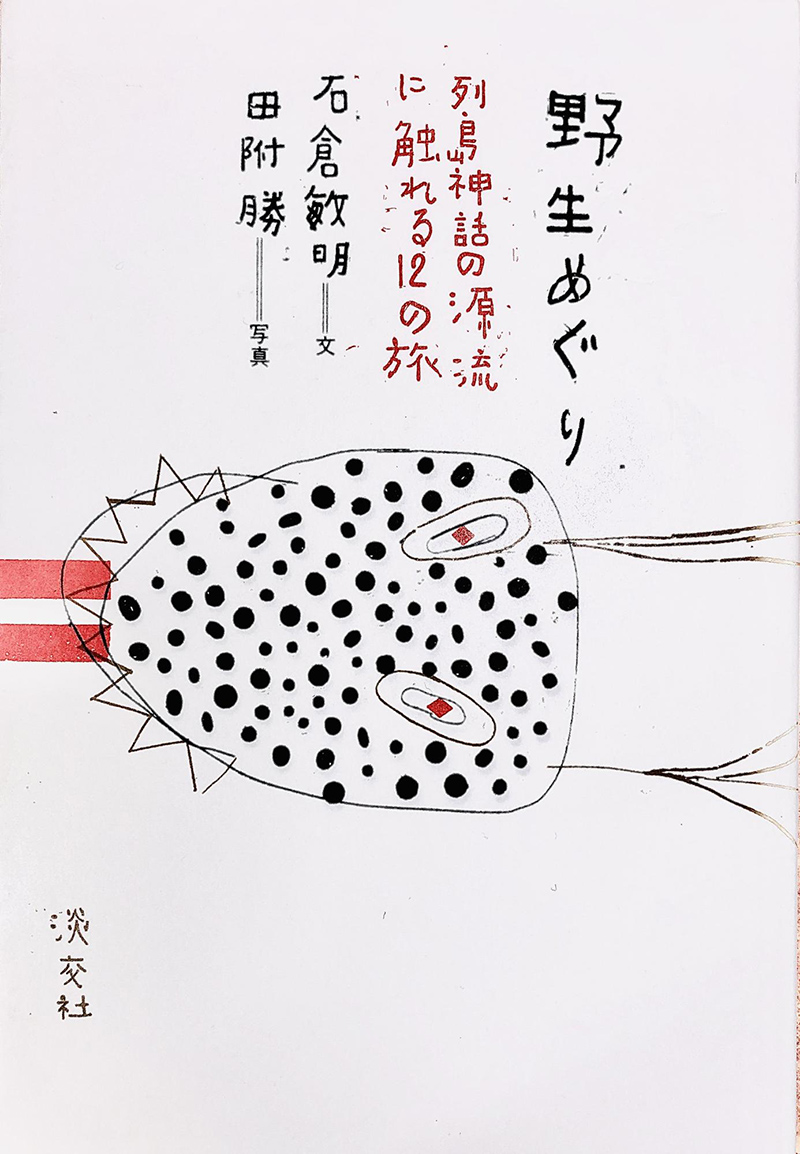

Are these the journeys mentioned in the book Yasei Meguri: Retto-Shinwa no Genryu ni Fureru 12 no Tabi*2 (The Wild Journeys: 12 Journeys that Touch the Origins of the Archipelago’s Mythos)?

Kamatsuda Shishiodori ©️Masaru Tatsuki

Kamatsuda Shishiodori ©️Masaru Tatsuki

Ishikura:

That’s right. Traveling for a year with Masaru Tatsuki from the Tohoku to the Kyushu region, across different lands, I often encountered foods offered to the various kami (divine beings) and memorial offerings for people’s ancestors and the deceased. At that time, I realized that the consumption of foods — agricultural produce, fermented foods like alcohol, miso, soy sauce, and fish and animal meat from the land and the sea is, across the lands, inseparable from the local faith in the gods and the Buddhist deities. From the experience of getting to learn about the backstories of the food culture of the various places, I couldn’t help but become sensitive to these “gifts from nature” that provide the energy for us to be active and form the bodies of each individual.

That is due to my experience with the nuclear disaster and radioactive contamination from the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. At that time, the wild plants and fish that were harvested in the Tohoku region were unfit for consumption due to radioactive contamination and there were significant restrictions on the shipment of agricultural and marine products. Paralleling these experiences, the site of the Minamata disease outbreak also had similar occurrences, which I learned about from Masami Yuki’s “Ishimure Michiko Ron*3 (Michiko Ishimure Theory)”. There exists a cultural sense, inherited from ancient times, to treat the local foods as gifts from the earth and the ocean; while in contradiction, those very gifts become contaminated with radiation and mercury, due to the expansion of human socio-economic activities. As I traveled for a whole year, I was trying to figure out how to use our imagination, pondering how to restore our body out of this asymmetric situation. In other words, I wanted to re-evaluate our body’s relationship with the environment through the food that connects them.

It also coincided with me moving from Tokyo to Akita. I rented a section of a rice field not too far from my residence in Akita. I had many experiences like farming with the children, playing in the streams, and gathering vegetables and herbs from the hills. Kosei Kikuchi — who practices no-till rice farming — opened a part of his farm as communal land and built a community where city-folk come on weekends to work on the farm.

On one of my days off, as I was casually plucking out weeds on the paddy that I had rented, I took a breather and gazed about at the satoyama around me, and I felt that there was no boundary separating the senses of my body from the surrounding environment; I started to see how I was connected to the space and the rice fields in front of me. At that time, several Japanese serows that had come down from the hills were walking in a nearby field. And in the paddies, countless living beings such as snails, frogs, and crayfish were eating and being eaten. Besides the crops that humans grow as food, the rice fields are home to countless small animals, insects, plants, and a vast array of microorganisms. In the intermingled world of such a large number of beings, I did a thought experiment to see if the realm inside my body is connected to the reality of the outside world.

I realized that the internal organs of our bodies are open to the outside world as a continuous tube via the mouth and anus. If you imagine expanding the internal organs like turning a glove inside-out, you can grasp that the surrounding environment, which is connected to food and other living things, is contiguous to your internal organs. Therefore, I think it is possible to regard our surrounding environment as our internal organs that are turned outwards; they are an extension of our body. That is the distinct image I had in mind when I came up with the concept of “external organs”. And thus, from the experience that I gained by traveling after the earthquake and by working hands-on in the paddy, I was able to get a sense of how a part of the limited space on earth communicates deeply with the insides of our bodies.

When I was in graduate school, I studied quite a unique theory called Taishōsei Jinruigaku*4 (Symmetrical Anthropology) from Anthropologist & Professor Shin’ichi Nakazawa*5. I felt as if I had gained a clue to understanding the symmetry in my way. This theory is the idea that “symmetrical logic”, which allows us to grasp the world in its entirety, and “asymmetrical logic”, which segments things and puts them in chronological order, occurs in complex manners within the human mind. In other words, the human mind comprises a “bi-logic” system comprising two parallel systems of logic: unconscious thought, which transcends space and time, and conscious thought, which tries to grasp the world rationally. I felt that that logic had come to fruition with my own bodily experience via the term “external organs”.

This tube that passes through our bodies, in fact, forms an intertwined loop that opens endlessly to the outside. I believe that by conceptualizing this loop as an “external organ”, we may be able to open a channel to understanding the world shared by the things that eat and the things that get eaten, while at the same time, connecting each individual’s body to the world outside.

We, humans, understand the reality of the hills and rivers that surround us as being units that extend outside our flesh and bone bodies. If we consider this to be “asymmetrical logic”, then parallel to it is the “symmetrical logic”, in which the beings existing in the outside world are like food that passes through the body. In other words, the act of eating something, digesting it, and turning it into energy, can fundamentally be understood as a kind of continuous entanglement of the internal and external organs. From another perspective, my own body may be a part of the external organs of others. The initial idea was to reconsider the internal and external organs as a loop that transfers energy, similar to mirrors reflecting each other.

§

Karasawa:

So nature is a form of our internal organs turned inside out. It feels like the body also extends into the world outside.

Ishikura:

If there are things such as nature within and nature outside, I think there are various perceptual interfaces that tie them together. For example, all of the diverse sensory organs, which comprise our five senses, connect to our internal organs — our body’s invisible, unconscious level. And, the deeper you dive inside, the more the circuitry of these senses is connected to the space outside. This spectacle that makes us aware of the entanglement of the body’s interior and exterior is what I have given the name “external organ”.

§

Karasawa:

That makes sense. One’s inside is connected to the others on the outside. So, an “interface” is a point where the distinction between inside & outside, closed & open, becomes ambiguous.

If the inside becomes the outside and vice-versa, to put it in extreme terms, when humans eat something, they eat a part of the extension of their self that is on the outside. It seems that it could be considered as consuming your own kind. Could we call it a kind of “cannibalism”?

Ishikura:

That’s right. The concept of “external organs” emerges when we connect our visceral experiences to the environment that lies beyond our skin. In essence, when we look at a mountain, we take this real space and enclose it in brackets called “nature”. We put them in a kind of cognitive enclosure. But if we take a closer look, we find that that very mountain is home to many different living beings at every moment; some are eating and some are being eaten. A real world comes to life there.

Put another way, there are numerous semiotic dimensions that occur there. Eduardo Kohn, who goes beyond just humanistic symbols, conveys in his book, How Forests Think*6, that there are large groups of ecosystems of “selves” there. Eating the beings that live there is connected to the peril that eating humans and eating other living beings flat-out mean the same thing. Once you’ve swallowed what you’re eating, you become unable to recognize what it is — whether it is the flesh of a human or that of a cow (citing a Japanese proverb, lit. “once it’s past the throat, one forgets the hotness of what’s been swallowed”). We carry these unconscious experiences inside our bodies, which are perpetually close to cannibalism.

However, in real life, we try to rationalize and stay away from such reality. It is as though we have isolated ourselves in a societal bubble that is like an enclosed island. If that is a kind of community, then I want to grasp the concept: being in perpetual contact with the intertwined realms of perceptions & flowing energies, which transcend communities, as the reality existing outside the internal organs.

§

Karasawa:

You expressed the idea as “we have isolated ourselves in a societal bubble that is like an enclosed island,” which implies that we have drawn a dividing line between what is essentially a connected situation and have rationally distanced ourselves from the target.

Ishikura:

That is exactly right. For example, the philosopher Descartes stated, “I think, therefore I am.” And, for example, artistic creation is based on the premise that “I draw, therefore I am.” or “I create, therefore I am.” Speaking in terms of the model of art that began in Europe: the main subject, which serves as the starting point, has been unable to come out of the Cartesian model of thinking. I feel that it is necessary for us to bring the “I” that “thinks” back to a point before the dividing line.

The “I” that thinks, creates or composes, unconsciously must always be eating something. It may seem as though we have rationally divided and pigeonholed the physical dimension; but, when we eat something, we open ourselves to the world outside, which simultaneously transforms both. The Cartesian self that “doubts” and “thinks” must also eat—such that it has the energy to think. Food, as an interface, is contiguous with a significantly transformative experience.

§

Karasawa:

I can understand that very well. So, contrary to “I think, therefore I am.” you also mentioned, “I eat, therefore I am.” and “Fukusūshu Sekai de Taberu Koto*7 (Eating in a Multispecies World)”. And, since humans need to eat for the energy to think for there to be an “I think”, I felt that you would consider that food exists as the most fundamental thing.

Using examples like the tale of Shashin Shiko (that bodhisattva offers his life to feed a tiger and her cubs) in Buddhism or the Shinto goddess Ōgetsu-hime (that her dead body produced various foods like rice seeds, wheat, beans, and so on), stories with themes about food convey something that is of great value in those religions. The story of Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruit is also extremely important in Christianity, but it also seems a little different in phase from Shinto and Buddhism.

I feel that the aspect of the “gift” is very strong in the stories of Shashin Shiko and Ōgetsu-hime. I think the aspect of genuinely devoting oneself is quite strong. While, on the other hand, the act of eating the forbidden fruit in Christianity’s Book of Genesis gives us a glimpse of something akin to the strength of human-initiated actions. Do you have any thoughts about the difference between the Christian world and other religions when it comes to food?

Ishikura:

In monotheistic religion, there is a mix of two mythological systems: the Old Testament and the New Testament; and, they have in them a specific worldview regarding food. In the mythology of Hebraism: it is by the very act of eating the fruit of knowledge that they were expelled from the pure, ideal realm and acquired physical bodies. Humans are expelled from the pure, spiritual world and fall into the dimension of “flesh” or the “corrupted realm” of sexuality and food, where animality and humanity intertwine. Mythologically, if we trace back to the premise of this worldview, the very snake that tempted Eve is also symbolic of ancient knowledge. That is because it is connected to the even older mythologies that came before Hebraism, from the Neolithic age.

Similarly, the Bible is also a source of dietary laws. When you read the Ryōri Minzokugaku Nyūmon*8 (Introduction à l’Ethnologie Culinaire) by Yvonne Verdier, you see that the narrative of God creating the world in seven days is still structured as the idea of food in the French countryside. On Sundays, which is the day of rest, the menu, food preparation methods, number of plates, and table manners are all different; people eat the meals in a different way than their food on weekdays — when God was creating the world according to the Book of Genesis. The kinds of animals to be used as food are also prescribed by God.

That is why in Christianity, people thank the Creator — the monotheistic God — before eating their food. It is more of a gratitude for God’s grace in giving us the food than gratitude for the animals and vegetables used as food. I think this is based on the premise of “Gratitude to the One”. In short, there is the idea that although there is a wide variety of ingredients, there is only one entity to be thankful for: the one who created them all. I think this shows isomorphism to the logical structure of anthropologist Philippe Descola’s Naturalism — “One Nature, Diverse Cultures”.

On the other hand, as opposed to Hebrew mythology, the background of the European worldview incorporates the different perspectives that arose in the polytheistic world of Greece and Rome. The ancient Greek and Roman myths were hidden from the stage of the monotheistic faith. However, they were actively represented in the world of artistic imagination: like the Temple of Artemis in the Mediterranean, which later became a center of veneration of Mary, or disguised in the form depictions of The Virgin and Child, belief in saints, and belief in angels among the monotheistic world via mythical translation. In essence, European art and philosophy were born out of this kind of a mythological cross-cultural translation system.

Nature is one, but cultures are diverse. It is an eclectic mix of monotheistic Hebraism with the diverse manifestations of Greek and Roman thought. We can arrange these anthropologically as mono-naturalism and multi-culturalism. Perhaps it is as Nietzsche said, “God is Dead” in the modern age,however, the God in Hebraism continues to remain as the “one” who supports physics. In contrast to that, “culture” has emerged as a system of diverse symbols and pluralistic values. Nihilism is nothing more than such a shift and segmentation. Multi-culturalism is precisely the Greco-Roman semblance of the world that ties together “diversity and fiction”. In other words, in the European system of cosmology that combines the one and the many using the dualism of nature and culture as its backdrop, the plurality of the experience of “food” may have been trivialized.

In contrast to Eurocentrism, to truly talk about food as a pluralism, I believe that we need to let go of the premise of a monistic nature using the perspective of multinaturalism. Then, via the Japanese custom of saying “Itadakimasu (I humbly accept with gratitude)” before eating, which is said with gratitude for the workings of the entirety of nature, to the lifeforms that form every ingredient, and to the farmers and chefs who provide the food, we can see its multifariousness.

The system where “things that get eaten” and “us who eat them” can confront is, of course, different from the mythology that regards the creators as absolute “others”. By tracing how the things that we eat, the environment in which what we eat is born, and we who eat are connected, I think we can decolonize our thinking and find a different way to reweave the relationship between nature and humans.

§

Karasawa:

In reality, humans can also be eaten. But as humans, we tend to only think that humans are the top predator and other animals are eaten by us. Look at how we have fenced animals in zoos as objects for human observation. At the root of this is the view that humans eat or observe, while animals are eaten or observed. This asymmetrical structure must be reexamined. What opens up when we become seriously aware of the possibility that humans can be eaten by these other species?

Ishikura:

If we start from the ontological premise of “I eat, therefore I am,” we can go one step further and infer that “we may also be eaten.” In other words, the fact that beings with a flesh body like us can be consumed inside the “external organs” of others allows us to conversely say that “I am eaten, therefore the world is.”

The internal organ perspective — “I, who eats” — cannot explain the existence of the world. This is because the food is already placed in the world. However, when we speak from an external organ perspective — “I, who am eaten” — the perspectives of multiple species appear. For the first time, we see a world of phenomenon and a world of entities that is crowded with that which is eaten. This is the basis of the external organs that guarantee the universality of the world and the universality of eating, and also the basis of the material dimension that supports the externality and mutuality of bodies.

Moreover, this material dimension is always supported by many “decomposers”. In the theory of ecology, three layers are discussed: producers, consumers and decomposers. For example, if you go into a forest, only a small fraction of living things there have a direct eat/be-eaten relationship. The overwhelming majority decay without being eaten. In other words, only a small portion are lucky enough to be eaten and used as energy by others, while the overwhelming majority decay without being eaten. However, these decaying beings are actually eaten by things that cannot be seen by the eye such as fungi and slime molds, or small animals and insects that are hard to see. I think that the multitude involved in the act of “being eaten” has depth from the perspective of circulation.

“Eating” and “being eaten” certainly do not have a pairwise relationship. We tend to model “eating” as something that is always a two-way relationship, like a romantic or sexual relationship. However, there are actually “one-to-many relationships”.

Moreover, in this case, we can imagine what pairs with the “many” as a gathering of the entire ecosystem, including the “one”. It has the feeling of being eaten by many; you could even say, “I am eaten by us.” We are always being eaten by the earth, eaten by nature, returned to all of the external organs that surround us. In this way, even large beings like us can decay and become part of the energy used by others.

Compared to forming a special relationship with someone, becoming food for this open “totality” may seem like a pointless death. But of course, it is certainly not pointless. So, if we are going to seriously consider the perspective of coexisting with things like bacteria and viruses, I think we will need to extend the idea of eating beyond a pairwise relationship between predator and prey.

§

Karasawa:

I think that’s exactly the case. To decay is actually to be eaten. When I die, I want to be eaten by slime molds, and when slime molds and bacteria eat, they cause decay. So, when a human is eaten, it is not only eaten by one specific entity, but also preyed on by bacteria and slime molds after being eaten and excreted as waste. I think that in this way, we support other lives and the world.

In that sense, too, predators and prey are not one-on-one. It’s one-to-many. It has now become rare for people to realize or fully comprehend this connection between being eaten and supporting the world. What is the cause of this?

Ishikura:

The progress of urbanization and civilization has created a system that no longer requires us to be directly returned to the soil. In that environment, even our appreciation for our connection with the soil can easily be forgotten. To overcome this and connect the circulatory system of nature with the circulatory system of human civilization, it will likely be necessary to revise the concepts of the “self” and the “body”.

As Gregory Bateson put it, the “self” of living things in a forest extends beyond the skin. This “self” may be dispersed among several bodies, or it may be scaled or scattered to various dimensions within the body, such as individual cells. Eduardo Kohn adopted the viewpoint of an “ecology of selves” on the basis of this sort of thing, which I think is very revolutionary.

This idea is also related to the experience of being eaten. In fact, to be eaten by a large number of entities means that the self is not demarcated by boundaries such as the skin of the body. Even in temporal terms, the self does not end with one generation of a single individual. So, animism becomes possible as a result of these “multiple selves.” Beyond the perspective of two entities in the eat/be-eaten relationship, we are actually eaten, decomposed, decayed and returned to the soil by a multitude of entities in preparation for the next generation of life. From this perspective, a different reality that guarantees the “ecology of selves” comes into view.

In the 19th century, anthropologists created an ideological model that portrayed animism as a simple religious belief at a primitive stage behind monotheism. This assumption by anthropologists may have stunted our thinking for a century. Kumagusu Minakata was perhaps the rare example to have noticed this. Now, by connecting the circulation of civilization with the circulation of nature, it has become possible to present a new animism, or rather a more appropriate model of animism. I think we are approaching the time when that must be done.

§

Karasawa:

Connecting the circulation system of civilization with the circulation system of nature seems like a difficult problem. Are there any overlapping parts?

Ishikura:

I believe that, fundamentally, all systems overlap. Artificial objects of civilization and the dimensions of nature always overlap. A Newar friend who I met in the town of Sankhu, Nepal, once said, “There is nothing in this world that has no connection to the body of the goddess.” In other words, non-dualistic thinking that does not separate artificial objects from natural objects supports the Buddhist goddess-faith of Newars. This kind of wisdom is taught in indigenous communities around the world, not just among Newars. Ecological consideration for natural resources and a sense of bioethics have also been inherited from this.

Capitalism presupposes a colonization of nature that has made us mistake the infinitely connected body of the goddess for the finite property of humans, while falsely believing that the limited resources of earth can be exploited without limit. Restricted by a model that focuses on human civilization, we have taken the things that surround cities lightly, exploited nature and damaged the environment. This has created very serious problems in what is called the era of the “Anthropocene”. A large and difficult-to-bridge rift has formed between metaphysical and socio-economic problems. What is forming here is a large gap between the finite and the infinite.

§

Karasawa:

Artificial objects in the human world are all actually made of things from nature. So, it could be said that every artificial object already contains nature. This also connects to Tathāgatagarbha thought: all creatures live individual lives, but inside each, there is something like a seed that can fully become the Tathāgata. The current discussion reminds me of that.

It also seems to connect to thinking about the relationship between “me and you” or “me and the world” while seriously confronting the eat / be-eaten relationship that was explained earlier. Could you tell us a little more about your impression of Japanese history and Buddhism, or about the idea of co-existence against that background?

Ishikura:

When looking at the development of Tathāgatagarbha thought in Japan, it seems to me that “hijiri” monks played an essential role. In the early period, there were two types of hijiri. The first type intervened in social spaces, such as Gyōki Bosatsu (Gyōki Bodhisattva). I think that this was a type of altruism that improved the environment for humans through social projects, such as river management, public works and the construction of large statues of the Buddha. At the same time, another type of hijiri pursued spiritual training in forests, such as the legendary En no Gyōja and Hachiko Ōji (Prince Hachiko), or practitioners of the Jinen-Chi-Shu (Nature Wisdom Sect) or mountain-forest Taoism. By making contact with an ecological reality separated from the human world, these hijiri attempted to perfect altruism from a viewpoint surpassing humans. For both humans and nonhumans were indivisible Tathāgata at their root, carried like an embryo. In the Heian period, a new ideology was born that connected the city and the mountains through the dynamic intersection of these two trends. This occurred against the backdrop of the divergence of Ritsuryo Buddhism and the mountain-forest Buddhism of the previous era. The so-called “hongaku doctrine” also developed from a reinterpretation of the Tathāgatagarbha idea that the Tathāgata dwells in both humans and nonhumans.

In other words, it connected well-populated zones of everyday life with training dojos set amid mountain sanctuaries, uniting human altruism with superhuman altruism. I consider this a prototype of Japanese Buddhism. However, when the political power of the city and the religious power of the mountains expanded, the human world and the religious world separated. When that happened, many sect founders came down from Mt. Hiei, sparking a religious renaissance known as Kamakura Buddhism. Japanese Buddhism has always been steeped in this sort of relationship between village societies and mountains, with various sects and Shugendo practitioners serving as mediators. It seems to me that, in this way, Tathāgatagarbha thought has left a rich history of ideas in the Japanese archipelago.

In the history of the Japanese archipelago, the lineage of this kind of Buddhist altruism and the world of gods from myths that have been passed down for generations merged to form a system of thought on the relationships of coexistence between people, creatures, nature, gods and the other Buddhist deities. This system of thought is known as shinbutsu shugo (syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism). If you look at the relationship between humans and nonhumans based on these relationships of coexistence, it is hard to capture society through a lens like “community”, where the composition of the world is restricted to humans from the beginning.

I believe that a concept of “Kyōitai (co-heterogeneity)” will be necessary. Co-heterogeneity is a model beyond the pure social community that guarantees communal uniformity. It seems to me that the world that surrounds humans is always “more than human”, and the societies that have formed throughout the Japanese archipelago have always been “more than community”. To put it another way, I think Charles Stepanoff’s concept of “hybrid communities*9” provides us with a better understanding of the multi-species world.

§

Karasawa:

It was Kizo Ogura who first used the concept of “Kyōitai (co-heterogeneity)”, right?

Ishikura:

That’s right. The philosopher Kizo Ogura conceptualized “Kyōitai (co-heterogeneity)” as a broad community of various regions in East Asia, such as China, the Korean peninsula and the far-east Japanese archipelago*10. After the Hatoyama Cabinet of the Democratic Party of Japan advocated for an “East Asian Community”, “East Asian Co-heterogeneity” was proposed as an alternative that respects the differences between each region.

In 2017, I stayed in Hong Kong for an art project exploring myth, history and identity in Hong Kong at the 20-year turning point since its return to China. My Korean and Japanese interpreter at the time introduced me to this concept, which impacted me greatly. I felt tempted to expand the concept significantly beyond its original context. In other words, I wanted to revise the concept to create hybrid narratives for stories that have been told within a framework of identity, such as the relationship between history and myth, the sphere of coexistence of different species and the relationship between the body and the environmental world.

§

Karasawa:

I feel that “co-heterogeneity” is in line with Kegon thought. For me, the term “community” suggests a gathering of members of the same species that share the same ideas, while “co-heterogeneity” aims for a kind of symmetrical relationship where different species coexist in a form that does not simply nullify the individual members. This seems similar to the Kegon concept of “jiji-muge hokkai”, the realm where individual phenomena interact without obstacles, and do you think there is some kind of connection between “co-heterogeneity” and Kegon thought?

Ishikura:

The co-heterogeneity model is based on the idea that we can connect individual living beings without eliminating the differences between those individuals, and in fact by using those differences. It encompasses the challenge of how to inherit pluralistic wisdom from the myths and cosmologies of each group by connecting differing ontologies without excluding the wide range of scientific achievements that humans have accumulated.

When we try to talk about science focused on human communities, we are forced to incorporate the modern premise of a “one world” as the remnants of the “absolute entity” — a legacy of monotheism. The anthropologists John Law*11 and Arturo Escobar*12 have criticized this “one-world world” as a colonialist framing of development economics that reduces the earth to a backdrop for human activity.

On the other hand, if there is such a thing as “wild science”, it would involve multidimensional politics that relativizes the humanity of humans. Human communities would not be at the center of the universe, with humans overlooking all other things and refashioning nature. When we break free from that kind of anthropocentric perspective and rediscover a kind of common world, the non-dualist and pluralistic teachings of Buddhism will be rediscovered.

To go deeper into the truth, “lemma” thinking reveals the perspective of the pluriverse. This cannot be understood within the framework of scientific logos, and it encompasses not just Buddhist thought, but also mythical thinking and indigenous cosmologies. How do you imagine something like this that cannot be fully expressed in the narratives of logos, and how do you realize it as a model for globalization? I think that the modern rediscovery of Kegon thought, such as Professor Nakazawa’s “Lemma Studies*13 (Scientia Lemmatica)” or the study of Kumagusu Minakata that Mr. Karasawa has consistently pursued, is directly linked to the contemporary question of co-heterogeneity.

Anthropologist Takashi Osugi has proposed a “community of nonidentity*14” or a nonessentialist “Creoleness and Alterity”. I have long thought that this might overlap with the Buddha’s criticism of essentialism in ancient Indian religions, such as Buddhist teachings on the logic of emptiness or the law of dependent origination. In other words, anthropological criticism of identity, which seeks to observe the reality of creoles and hybrids, seems to have a high affinity with Buddhist logic.

If groups of humans and nonhumans are materialized without guaranteeing this “nonidentity”, under Kohn’s argument that forests can think, we would need to assume an idea of a “forest god” idol, materializing entire forests. However, indigenous societies have a mechanism to prevent this from happening, creating a situation where multiple species constantly engage in pluralistic competition while the “open whole” is maintained. I believe that a “community of nonidentity” or “co-heterogeneity” is also generated here.

§

Karasawa:

I see. Buddhism has now been associated with multispecies issues, but I wonder if this might have some connection to the Japanese word for species, which also means “seed”. In short, seeds were sown on the Shinto soil of Japan, which absorbed the energy of the soil and produced flowers. You could say that this is the so-called shinbutsu shugo (syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism), and I view it as a method for the development of Japanese-style Buddhism. How did Buddhism produce flowers when it came to Japan? It seems necessary to examine that method.

Ishikura:

It is certainly appealing to think of Buddhism as multiple “seeds”. I have imagined Buddhism as a plant with roots spreading through the Earth, from which performances and architecture have spread throughout the lands of Asia.

When I was a graduate student doing fieldwork in northern India, at one point I ran out of money and hit a wall. So I attended a Buddhist festival in a Buddhist holy place named Bodh Gaya in order to cool my heels for a while. When I experienced that sudden gap in activity, I had an unexpected realization.

In the holy place of Bodh Gaya, where Gautama Buddha was said to have attained enlightenment, there lies the temple building of Mahabodhi Temple. As you know, at the heart of the temple sits the simple “The Vajrasana (Diamond Throne)”, which is a monument to the path of becoming a Buddha, and behind the throne grows a single bodhi tree. Of course, the tree has been replanted for many generations, but when I saw that tree I understood that Buddhism is a single tree.

Whether he was living in a castle as a prince of the Shakya clan or experiencing unimaginable hardships as an ordained practitioner, Gautama never achieved the kind of spiritual enlightenment he was striving for. However, it is said that when he abandoned asceticism and came down from the mountain, he sat in front of this bodhi tree and finally discovered the law of dependent arising which underpins the world. This famous tale could certainly not be told without a plant such as the bodhi tree growing in this place.

Gautama transcended his individual psychological dilemmas to perceive the reality of the world beneath that tree. I think this has a profound meaning. As I sat in a meditation park near the bodhi tree in a trance, Buddhists from various regions such as Tibet, Mongolia, Nepal, China, Thailand, South Korea, and Japan all came to visit that holy place, but their prayers were entirely different. It is a sight never seen in Christianity or Islam, but just as you said, it seemed as though the people of each country had transplanted the seeds of Buddhism into their own ideas and expressions, allowing them to grow into different fruits.

Thus, the diversity within the world of Buddhism is significant: the temples from each country in Bodh Gaya have different architectural styles, and each country’s way of worshiping is subtly different. The sutras have also been translated into various languages, and different peoples have different etiquette for prostrating themselves. However, the people in prayer all face toward the same solitary tree. There are no images of Buddha or gods — just a single bodhi tree.

Of course, in front of the bodhi tree sits the Diamond Throne, a simple “place”. There is a single tree and a place for a person to sit. I believe that all of history begins from the relationship between “place” and “plant”. It does not begin from gods or from a holy scripture. There are simply “plants”, which are the original inhabitants, and a “place for people to sit”. The existence of Buddha is adjacent to us humans and is a theoretical ideal of an “enlightened one” open to all people. This leads to the enlightened vision that anyone has the right and the ability to sit beneath this bodhi tree.

This idea reveals the history of the soul, which is, as you said, that Buddhism’s seed — or the “bija” of enlightenment — was carried to a distant land, planted, and allowed to flower and bear fruit. Buddhism being transplanted into the Earth is adjacent to the ancient mythologies which have persisted in each region. The seed is carried from one land to another land and allowed to take root; it is cultivated; its flowers of wisdom bloom and it bears fruits of benevolence; it passes from generation to generation. I think Buddhism gives us just such a model of an ecosystem of plant mobility.

§

Karasawa:

People with different languages and different ways of praying all surrounding a bodhi tree, instead of an image of Buddha—that’s an interesting picture. A soft center instead of a strong center would in fact function as something to connect people with different ways of seeing and thinking. “co-heterogeneity” was an important topic of “Cosmo-Eggs*15”. How was it realized within the artworks there?

Ishikura:

I appreciate you reading about the Cosmo-Eggs project. I don’t think that “kyōitai (co-heterogeneity)” has never not been realized — one might even say that it is always present. Having said that, when it is materialized, something important may be lost. Perhaps we should view kyōitai as an imaginary collective with the potential for creation. The reason we were partial to the “egg” model is we wanted to imbue it with an image of an unborn world.

At the same time, we wanted to share a concrete image of coexistence and symbiosis which would work in the anthropocene age by using the small places known as “Tsunami Boulders” scattered about the Yaeyama and Miyako Islands in Okinawa. In fact, our collaboration arose due to the series of video works called “Tsunami Boulders” which was shot by artist Motoyuki Shitamichi on the outlying islands of Okinawa.

As you know, tsunami boulders are enormous rocks which were once on the ocean floor but were transported onto dry land due to the shocks of large earthquakes and tsunamis. In other words, these rocks are monuments to large disasters in the past. Meanwhile, Mr. Shitamichi’s video works of these tsunami boulders show migratory birds called terns building nests; small creatures crawling across the boulders; moss and plants growing on them; island residents harvesting sugar cane with farming implements; and children taking commemorative photos in front of the rocks. In other words, the tsunami boulders were a perfect microcosm which presented a model of “co-heterogeneity”, i.e., the open whole, through the collective of different things around them.

From a scientific perspective, most tsunami boulders were originally coral limestone which sank into the sea and was adhered to by fossilized marine creatures. In fact, coral is a living organism which is in symbiosis with an alga called zooxanthellae, and even after being washed up by a tsunami, it continues to form a symbiotic domain with many flora and fauna. That is to say, trees and plants grew abundantly atop the rocks and became habitats for a variety of birds.

The tsunami rocks are believed to be holy places and have been used as special burial grounds. Even so, they are also play structures for children in parks, and some tsunami rocks even act as walls for people who build their own abodes next to them on Tarama Island. Thanks to curator Hiroyuki Hattori, the Cosmo-Eggs project presented a model of symbiosis between humans and non-humans expressed through the tsunami boulders and their connections with other diverse beings*16.

As a response to Shitamichi’s work of discovering the diversity surrounding tsunami rocks and making it into a series of video works, composer Taro Yasuno recorded the birdcalls of local birds and composed a piece which vividly reminds one of oviparous myths, where people are born from eggs. He then created an installation where this piece is automatically played on mechanically controlled recorders. Within the Japanese pavilion, a historic edifice with a hollow center, architect Fuminori Nousaku created an installation which carefully comingless the various approaches of the participating artists to manifest the idea of modern ecology. The mobile screen which projects Shitamichi’s video imeges, the map case and appliances; the balloon and recorders installed throughout the space which produce Yasuno’s music — all of these things make up the collaboration among Nousaku and the other artists.

From my fieldwork in Miyako, Yaeyama, and Taiwan, I gathered tsunami myths and oviparous myths. I used these to make a creation myth that a new humanity was born not from the womb but from eggs, and other artists engraved the myth onto the walls of Japanese pavilion. Through my fieldwork in the southernmost islands of Japan, an artist, an architect, a composer, an anthropologist, and a curator created an exhibition project in Venice. I think it was an experimental endeavour which has seldom been undertaken before*17.

§

Karasawa:

“Co-heterogeneity” always has dynamic movement, and in a way, it is the process itself. The other day I was at the domestic exhibition in the Artizon Museum, and I was impressed by how vibrantly the process was expressed. The timeline and process of the Cosmo-Eggs exhibition was written all over the walls, in a co-heterogeneitic way.

A very interesting thing about Cosmo-Eggs is that it is forever changing. When people sit on the balloon in the middle, the air is carried by tubes to the recorders, which react to each other and always produce a different sound. To me it seemed to hint at a dynamic form. Next, the wheels on the screens interestingly show the possibility of motion without moving. By indicating mobility while stationary, static and dynamic coexist, letting us imagine dynamic motion while at rest. It felt like a very co-heterogeneitic installation.

Yours was a group of people with different areas of expertise searching for a co-heterogeneitic way of collaborating while sharing understanding, production, and practice. How did you reflect the concept of “co-heterogeneity” in the creation myth that you wrote for the project?

Ishikura:

One characteristic of this project appears in the fact that, in addition to intensive fieldwork, our members were scattered across Japan but we continued to use online communication for our meetings. In other words, we made frequent use of technologies such as online meetings — which became commonplace after the impacts of the coronavirus — to better understand each other. I joined our first online meeting from Akita, and I recalled the oviparous myths which I had learned about almost 20 years earlier during a trip to the Miyako Islands.

The title of “Cosmo-Eggs”, which was decided upon at that meeting, of course refers to the mythological “cosmic egg”, but its background also contains the oviparous myths. There is a myth of conception by the sun which is connected to a place called Uharuzu Utaki — also known as Onushi Shrine — on Ikema Island, in which a young woman is exposed to the sunlight and lays eggs. Within the creation myth, this myth is recounted together with the tsunami folktales also handed down on Miyako and Yaeyama Islands. The reason they are paired is that the former “egg mythology” is a story of the beginning of the world, while the latter “tsunami mythology” is a legend of the world’s ending.

Mr. Shitamichi’s video works and Mr. Yasuno’s composition and music-generating installation in fact have something in common: iterative structure. The tsunami myths and oviparous myths which I surveyed are each from different lineages which never intermingle. However, by handling them both successively I hoped to evoke the long history of the region, in which disasters such as earthquakes and tsunamis recur iteratively, and in which humans and other creatures continue to survive them. After that, the twelve eggs laid by the young girl just happened to correspond to the twelve recorders installed in Mr. Yasuno’s exhibition space; and the metaphorical visual elements such as the sunlight streaming through the ceiling of the Japanese pavilion and the egg-yolk-like balloon all came together. Gradually, it acquired an unintended inevitability and commonality.

However, I was not able to find the missing link which connected the tsunami myths and the oviparous myths until I finally visited Taiwan in January 2019. As the deadline for writing the creation myth drew near, I left Japan’s borders from Okinawa and went to survey the local mythologies of the indigenous people of Taiwan. By chance, I found a myth which connected those two story forms. In the area of Taitung, Taiwan, I found motifs such as ancestors being born from large rocks strewn about the coastline, or ancestors laying eggs after surviving a flood. These were a group of myths of ancestors appearing from the minerals near the sea just as a chick hatches from an egg. When I found these myths being told in Taiwan, an overall image of the creation myth finally emerged.

Rather than writing my own mythology as a storyteller, I wanted to liberate the mythology of the beginning and end of the world from the national unit and reconstruct it from the sense of cosmology of multiple islands by collecting myths from the Sakishima Islands, which is the southern limit of Japan, and from Taiwan, which is beyond the national borders. When I finally found the “stone egg” myth in Taiwan, my work surged forward and neared completion.

The creation myth I produced contains not only folktales but also my own personal imaginings, and I wove in some fragments of events I heard from the other project members and local people, too. Furthermore, there is significance in the fact that the sun conception myth of East Asia is related to the association of male or female single-gender groups. Our group ended up being composed entirely of men, so rather than from the womb, I focused on the story form of our ancestors being born from eggs. This led to thinking about birth and life on a plane higher than humanity’s.

§

Karasawa:

The members of Cosmo-Eggs are indeed all male. In a single-gender group it is especially important to think about the opposite sex; had there been a female member on the project, the artworks may have been slightly different.

The development of a young girl laying eggs after being exposed to the sunlight seems to hide many important elements, which I found fascinating. After receiving the “gift” of light from the sun, the young woman, who is yet to reach adulthood, lays eggs like a reptile. This far exceeds the physiology of humans. Starting with the “gift” of light, it expresses states of “co-heterogeneity” through human and non-human, adult and child. I think you used that as a big clue for the writing of the creation myth. It seems to me that an anthropologist would have to be quite brave to create a myth. Did you receive any comments from other anthropologists?

Ishikura:

Anthropology in Japan is currently developing away from its traditional systems and becoming more diverse and rich in its expression. Therefore, our work may be received as part of an experimental process which is trying to find ways of collaborating between art and anthropology.

Of course, a pioneer of this kind of experimentation would be Shin’ichi Nakazawa, who wrote a Yukar*18 (Ainu oral saga) to Matthew Barney. A series of such texts should exist, positioned between critical observations and poetic practice. Anthropologist Nahoko Uehashi wrote novels and stories, while Ursula K. Le Guin — daughter of anthropologists Siodora and Alfred Kroeber — wrote The Earthsea Cycle*19, which contained plenty of mythological elements. The path which connects such creative texts to ethnographies-as-anthropological-records has been secured after many hard fights since “the Crisis of Representation”. From the mid-20th to the early 21st century, anthropology, history, mythology, archaeology, sociology, psychoanalysis, and the arts have entered a period of rebuilding. Out of that process should arise the possibility of creative practice.

§

Karasawa:

Professor Nakazawa also presented a creative text before you. Come to think of it, I feel like “Kenji in Four Dimensions*20 (Yojigen-no-Kenji)” was a similar expression. Professor Nakazawa saw the potential in Kenji Miyazawa*21 and Kumagusu Minakata*22 before anyone and continues to present re-evaluation of the texts.

Ishikura:

That’s right. And Professor Nakazawa received that creative spirit from many who came before him. For example, in folklore studies there is Tōno Monogatari*23 (The Legends of Tono) by Kunio Yanagita and Kizen Sasaki, as well as The Book of the Dead*24 by Shinobu Orikuchi; a genealogy of scholarship which includes storytelling has been created; in French anthropology, Claude Lévi-Strauss and Philippe Descola tried a method of including very poetic creations in a text. Like Romania’s Mircea Eliade, there are theologists who have delved into research in both academia and literature. Therefore, one might say that re-examining storytelling is an important issue for art anthropology.

Furthermore, I expect that there will be much development in collaborations between anthropological practice and domains such as music and drama, modern art and environmental design, as well as methods of expression other than visual media and the relationships between various materials. To that end, we must not constrain anthropology to knowledge-generation, but instead we must forge it into an interface which acts as a bridge across the borders between other academic fields and art.

§

Karasawa:

I feel there is a connection to my research of Kumagusu Minakata hidden there. He realized the potential of storytelling through vast correspondence and records, and it remains an unexplored domain of knowledge. Just as Minakata grasped the logic of life through his research into slime mold, I sense that it will become crucial to link science with a variety of artistic domains in the future. Thank you for your time.

§