Shigeki Moro:

I would like to ask about the background of the philosophy you developed using classical Eastern texts, in particular Buddhist ones.

Takashi Shimizu:

While I did familiarize myself with classical texts from India when I was a child, I also feel that modern Western thought in this century has begun to once again trace Eastern logic. The ideology up until the 20th century asserted that dualistic thinking such as subject-object dualism needed to be overcome, and even German idealism had such thinking. However, with two mutually opposing extremes such as subject and object, there were many who thought to blur the boundary between these conflicting ideas and take the middle way, i.e., “A” and “not A.” For example, I think that Derrida’s deconstructionism is just such an ideology.

However, traditional Indian thinking has a fourth option which is none of “A,” “not A” and “A and not A”: the tetralemma, which is “neither A nor not A.” Traditional Western thinking would say that logical thinking is to choose “A” or “not A,” and that once “A” or “not A” is chosen the middle is no longer valid, i.e., the law of excluded middle. But the people of India are not convinced; they constantly think of that which cannot be reduced to either “A” or “not A.”

As it so happens, modern philosophy is again starting to think about such things. Philosophers such as Graham Harman say that an object cannot be reduced to internal constituent elements, nor can it be reduced to the external context surrounding it; such a neutral unity is an object. Until now it has been reductionism either way. Even smaller particles are aggregations of various properties and are therefore composed and cannot be the starting point for building gradually larger things from the bottom up. The idea is that anything is a neutral thing which cannot be reduced to either internal or external elements, and such things mutually subsume each other and create the entire world. This idea can be taken as a networked worldview, which connects to the issue of “the one and the many.” I think this is very close to the world conceived by Buddhism.

Every few years I go through a cycle in which I become completely absorbed in Buddhism and cannot think about anything else. In particular, I’ve been constantly reading Dōgen*1 and Nāgārjuna*2 since last year. Only a small fragment of Buddha’s thought has come through, one part of which is “the middle way free from two extremes (neither constant nor interrupted),” a unique way of thinking which states that the world must not be reduced to either “being” or “not being.” Another thing is so-called ENGI, “dependent arising.” All I know is that, apparently, at the time there was an ideology of JYUNISHIENGI, “the twelve links of dependent arising.” Although the various philosophies of early sectarian Buddhism developed from there, I think that the issue of how to overcome the law of excluded middle, which I mentioned a moment ago, how to overcome the law of excluded middle while reducing to neither dyadic opposition was an extremely significant issue.

For example, I believe that they were already making such efforts at the time of the Sarvāstivāda*3 sect, which was the main target of Nāgārjuna’s criticism. When making judgments using Western logic, usually in a phrase such as “Socrates is a human,” a discrete subject is subsumed in a predicate, this is considered a “judgment.” Once Socrates is included in humanity, we can no longer say that Socrates is not a human. This logic uses the law of excluded middle. Furthermore, if we say “Socrates is a human” and “humans die,” then the logic becomes layered. In contrast to this, the negative form in India does not in fact use only this type of logic. Apparently, Indian people think that the negation of “this is a pot” and the negation of “there is a pot here” are different.

§

Moro:

That’s true. They have absolute negation and relative negation phrasing. One form of negative results in an affirmative for something else, while the other way of negating says nothing at all about anything else and simply negates.

Shimizu:

That’s right. There are two ways of thinking here. There is a philosophy which attributes multiple properties to a subject and says “it (the subject) has these properties.” Schelling’s thinking was just such a philosophy. For example, if we say “an isosceles triangle is a triangle,” the subject “isosceles triangle” belongs to the predicate “triangle,” but we can also use the phrasing “a shape with two equal sides,” in which case a square or a regular hexagon or many other shapes may be in the group. In this way, there are those who say that not only does the subject belong to one predicate, but rather we can conceive of various properties belonging to the subject.

The important thing is when we say “there is something,” if we think of it as belonging to the subject, then the law of excluded middle is not applied. The ideology of Sarvāstivāda has something called HŌU (the existence of dharmas). They take “there is X” and subjectify the “condition.” They subjectify it and within this format where “condition” exists, various phenomena occur. By doing so, they notice the existence of something which transcends the law of excluded middle, a protagonist or cause of this state or action. The protagonist (subject) born in this way also has this condition, and because the subject does not have the hierarchical nature of those used in Western logic, it cannot be the object of a negative judgment. If such a subject could be conceived of, we must accept its existence.

This is what they call HŌU, and I think that they tried to affirm the world itself using it. However, Buddhism has Nāgārjuna’s criticism of the subjectification of the predicate, of the “condition,” so I considered how thorough his critique was in chapter two of The Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way (Mūlamadhyamakakārikā).

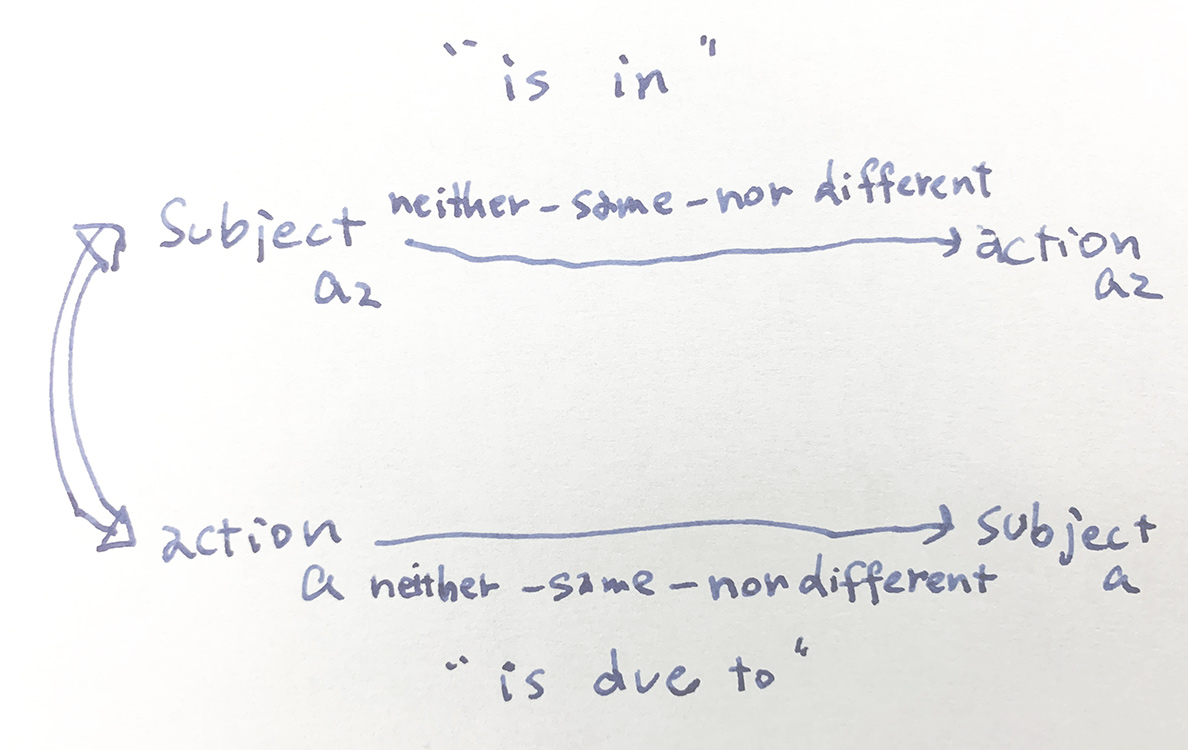

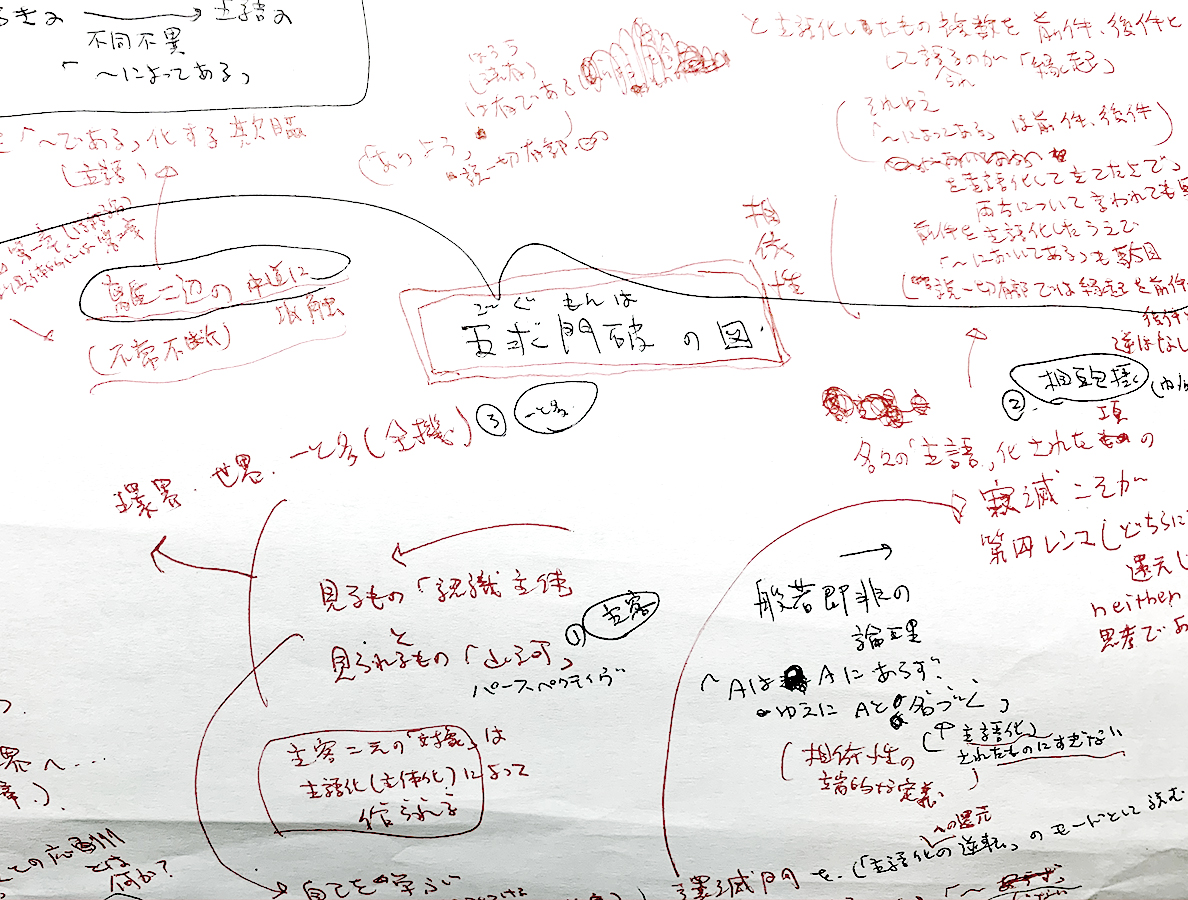

He uses strange phrasing, such as the subject being two-fold, or the action, i.e., the condition, being two-fold. What is he trying to say? For example, let’s say there is “action A” which we subjectify into “subject A.” Subjectifying it means making it into a cause, but now it’s as though “subject A” was there from the beginning. Let’s call this “subject A2.” By doing so, we now have an explanation where it was as if “subject A2” was there from the beginning and from it came the action. This in fact is “action A2.” These are in fact cyclical, and Nāgārjuna is saying that “subject A” and “subject A2,” “action A” and “action A2” are in fact duplicates.

Although we created the subject from the action, in fact, an action comes from a subject, so this is “action A2,” isn’t it? Although it has been deemed a subject here, actor 2 (subject 2) is in fact duplicated. Nāgārjuna very insistently says that this cycle is false. The general structure can be explained with the diagram above, where “subject A2” and “action A2” have “is in” written at the top, denoting an “inclusive structure.” In contrast, “subject A” and “action A” on the bottom have an “is due to” structure, meaning “due to this action, this subject exists.” When this cycle is generated, “there is X” somehow becomes “this is X.”

He tenaciously questions the deceit of that idea. With subject and action at each extreme, one side is set as the cause and the opposite becomes the consequence, or conversely, the other side is set as the cause and its opposite is now the consequence; this is in fact cyclical, says Nāgārjuna, and so you can’t make this claim. That is why he insistently points out that this is false; we cannot say that the subject comes from the action and that the two are the same thing. However, it is also strange to say that the two are distinct and exist separately, he says, so a relationship must form between “action A” and “subject A” which is neither-same-nor-different. The relationship formed between “subject A2” and “action A2” above must also be neither-same-nor-different. Each of these can be found stated one by one in some verses or other in the chapter two of Nāgārjuna’s The Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way. Putting it all in a very simple diagram looks something like this.

§

Moro:

That’s true. And he says that it is strange for the action to become two-fold.

Shimizu:

Duplication is very difficult to understand, but in order to explain it he says it is strange for “the leaver” to additionally “leave,” and he uses a phrase like “neither coming nor leaving.” It is easy to say that as a paradoxical negation, but the essence of the argument is difficult to understand.

Referring back to the cycle being a falsehood, what Nāgārjuna is in fact thinking is that the structure conflicts with the middle way free from two extremes, it conflicts with the tetralemma. By making “there is X” into a subject, it in fact becomes “this is X.” It is a reductionism which attributes causality alternately to both extremes of an oppositional dyad and therefore does not fulfill the middle way free from two extremes.

In the end, although they sought to take the dimension of a “there is X” event and use all of it in a tetralemma-like way, they subjectified everything such that it conflicted with Buddha’s original tetralemma of “neither being nor not being,” and I think Nāgārjuna’s main issue was how to deal with this. ENGI is expressed as “A exists so B exists,” “B exists so C exists,” but in fact, it is a chain in which everything is subjectified. We first must acknowledge that each subject is a loop.

Furthermore, for a subjectified antecedent and consequent, some say that the consequent exists because the antecedent exists. Nāgārjuna thoroughly proves that we must reword this in order for it to be true and say that from the antecedent’s perspective the consequent exists, while from the consequent’s perspective the antecedent exists; they should be in a mutual loop. Therefore, in The Verses of the Middle Way, “exists due to” and “exists in” are repeatedly negated from both antecedent and consequent? He logically and meticulously crushes all of these possibilities.

What is important here is that the antecedent and the consequent must mutually and simultaneously subsume each and because of this we cannot say that one “exists due to” or “exists in” unilaterally from the other. Chapter two of The Verses of the Middle Way thoroughly considers this point. This is where the idea of interdependence arises – any A exists due to not A, and not A exists due to A. Therefore, the idea is that it does not exist due to “its own nature” but from its lack of self-nature, or KŪ (emptiness).

§

Moro:

One thing you said which resonates with me is that this discussion written in Nāgārjuna’s The Verses of the Middle Way has often been referred to as “transcending logic.” It is said that “emptiness transcends words,” and as one prepares this idea as a tool for modern philosophy, it seems that you are aware of how very logically Nāgārjuna constructs his theory.

Shimizu:

That’s right. He does not waste any words, and as you think one by one about each odd-sounding thing he says, there is a reason that it absolutely must be said. “What exists because of what, and then, what exists because of what…” – in order to make this non-reductionist, we should say neither that something “exists in” and make that extreme a subject, nor should we refer to the opposite extreme. We must conceive of saying both “neither A, nor not A,” or “neither not A, nor A,” simultaneously.

In doing so, what we call ENGI must not simply be thought of as the actions of things which have all become subjects. In order to refute them becoming things that simply “exist,” as in “X exists,” we must say that this exists and that exists mutually, and we must also think that that was the trigger for their subjectification; we must create a logic which simultaneously negates both extremes. For example, D.T. Suzuki gave in his Logic of Sokuhi an example of the metatheory unique to Buddhism which denies the law of excluded middle: “A is not A. Therefore, it is named ‘A.’” This logic appears endlessly in The Diamond Sutra.

§

Moro:

That’s true. The Diamond Sutra goes on endlessly about that.

Shimizu:

What the “naming” refers to is none other than subjectification. “Naming” is to temporarily subjectify a phenomenon, which requires a trigger for its being attributed to the subject. However, this forces us to create a situation where it cannot be the unilateral object for the reduction of the cause, nor can the counterpoint “not A.” This is important. This proof that the two extremes are neither-same-nor-different is called ICHIIMONPA by the Madhyamaka*4 school.

§

Moro:

“To destroy the same-different approach.”

Shimizu:

That is what Jizang (549-623) of the Sānlùn Buddhism called this theory. “One” and a “different” thing, “A” and “not A.” when looked at from either side are neither-same-nor-different; this is ICHIIMONPA. This theory was rigorous and ICHIIMONPA could be said about anything and everything. If action is cognizance, then, and of course I’m subjectifying here, there is a cognizing protagonist, but because of this, there is cognizance (object as condition). They are neither separate nor the same; they are neither-same-nor-different. However, if they are a single unit, then a meta- ICHIIMONPA exists. This creates something like an umwelt.

The cognizing protagonist and the cognizance, the subject and the object world are each in interdependence, so they double and redouble. ENGI had in fact become something like subjectified “A” exists so subjectified “B” exists. Looked at on a micro scale, “action A” <-> “subject A,” but “subject A2” and “subject B2” are also a loop, as in “subject A2” <-> “subject B2.” Based on this logical premise, if we continue to think step-by-step, an umwelt comes into being. The subject and object of the subject-object pair form an umwelt through the multiple layering of their interdependence.

The world is created when a protagonist begins to act, and the actor is created by the world; this relationship is gradually developed. If you read the theory of ENGI expansively, the intrinsic loop of action and subject becomes even more multi-layered, becomes ICHIIMONPA, becomes a sort of meta- ICHIIMONPA, and even a meta-meta- ICHIIMONPA. Thinking in this way leads us to conclude that it was a problem of “one and many.” Due to the multi-layered interdependence, “one” and “individual” are neither-same-nor-different from “many” or even “the entire world.” The worldview of “one equals many” gradually comes into being. The ideology of the Lotus Sutra was also mixed into this, and later it would be developed in the Buddhist way, but the original logic was Nāgārjuna’s ICHIIMONPA. It means that “one” and “the individual” are inseparable from the world. From what Nāgārjuna said while searching for logical inevitability, many logics emerged which mediate a variety of dyadic oppositions through ICHIIMONPA. This leads to a variety of starting points for the Mahāyāna Buddhism, which emerged in later years.

And at the same time as the umwelten emerged, so too did perspective: the views of the world itself, and what Dōgen duly called SANGA, “the mountains and water.”

§

Moro:

What you’re saying about the subject and object and the formation of umwelt sounds exactly like what is said in Genjō Kōan*5 of Shōbōgenzō*6.

Shimizu:

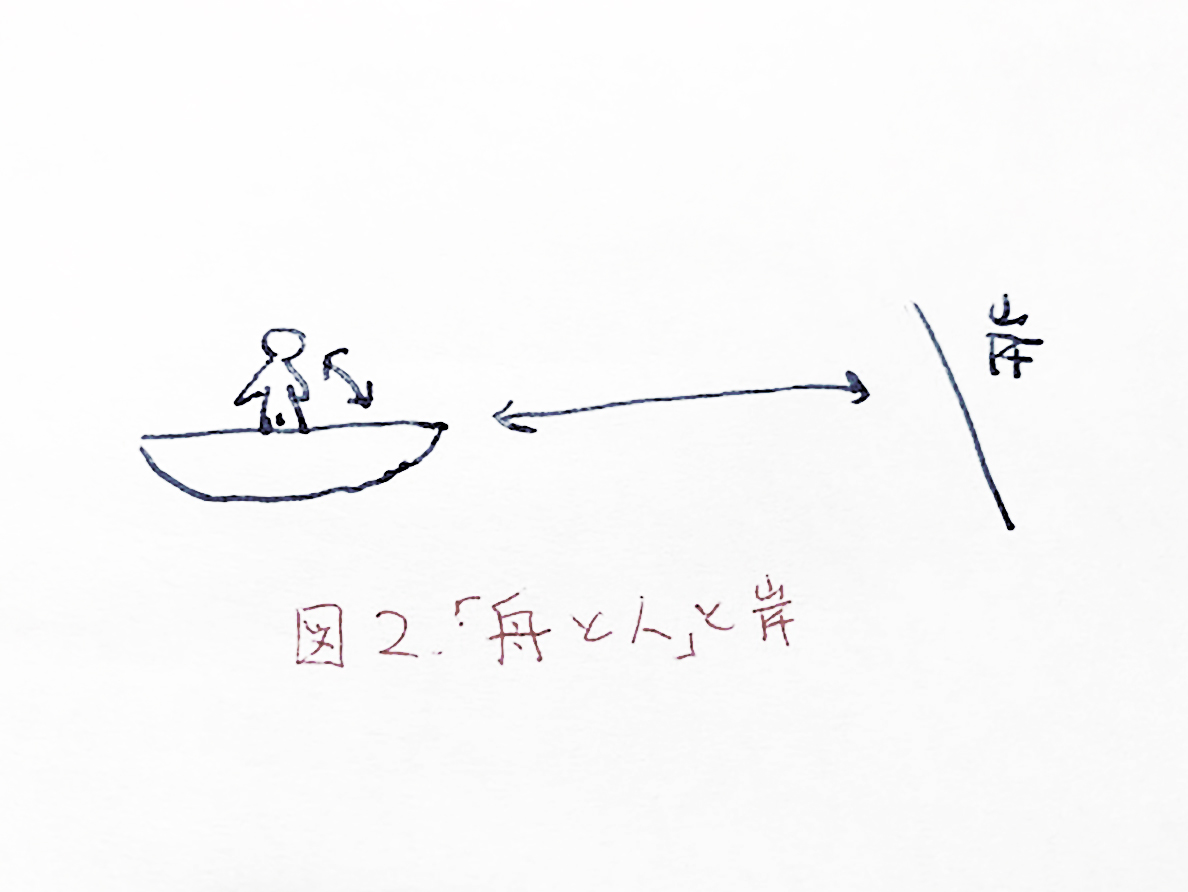

It is the same thing. You see, when we talk about “the subjectification of this and this” it may sound like an abstract discussion, but you have to start your thinking there in order to understand Dōgen. For example, Dōgen says that if you don’t focus on the boat but look directly at the object, it seems as though the shore is moving; whereas if you look at the boat you’re standing in, you realize that you are in fact moving. He is saying that one should think about the small loop of each umwelt one finds oneself in as well as the larger loop of the world. Once one thinks in that way, the individual’s tetralemma-like independence and their fact of neither arising nor ceasing emerges.

Also in Genjō Kōan, Dōgen says firewood becomes ash: the firewood has both a before and after, and the ash also has a before and after. Each of them is in a HŌI, a “dharma-state.” He also says that life and death are similar to these. This means that there are smaller loops and that each thing is not simply subsumed. Indian Buddhism is not just a meta-logic; it is a complete philosophy. It thinks in multiple layers of avoiding reduction of one part of an oppositional dyad to the cause. That’s why if one develops thoroughly the ideas of “there is X” and “this is X,” they arrive at the idea of perspective. This is exactly what Dōgen develops from.

§

Moro:

Normally Nāgārjuna is said to take a stance in opposition to realism, isn’t he? But with what you’ve just said, I find it very interesting that he seems closer to what is being said in modern philosophy’s New Realism or the Philosophy of Things.

Shimizu:

Harman says that objects exist all the more because they are not reduced to either internal or external; the logic has a single prominent thing. Buddhism thinks of the theme of subsuming, as in “exists in,” as a mutual thing, which is primarily developed as the issue of “one and many.” Because Buddhism treats “reducing to neither side” from the viewpoint of interdependence, which was considered at a glance to be the exact opposite of reality and objects, the truth is that they are two sides of the same coin.

§

Moro:

Can you explain what you said a minute ago about “perspective” in a little more detail?

Shimizu:

I think that one characteristic of Japanese Buddhism is that it thoroughly develops that idea. Looking at the discussion up to now in reverse, it becomes clear that that is what Dōgen was in fact doing. As I said a moment ago, if there is a boat with a person in it and an object such as the coast, then the coast object and the person object are body and mind, circumstantial and direct; they each mutually generate the other. Moreover, although the coast = umwelt, all of these elements are completely mutually subsuming; for example, the coast cannot unilaterally be the subsumer. Each becomes the focal point of subsuming. In that case, “one” equals “all.” For example, when a bird flies in the sky and becomes one with its umwelt, the sky itself is related to a further meta-sky. If we then think about the loop of the umwelt itself and the loop of the meta-umwelt, it is not an issue of locating whither or whence the bird flew.

§

Moro:

That discussion comes toward the end of Genjō Kōan, doesn’t it? “A bird in the sky, wherever it flies, finds the air unbounded.”

Shimizu:

That’s right. If I am on the boat and the coast is opposite me like so, there is an inseparable relationship between us. If we also consider the relationship of the coast here, this loop becomes multi-layered, and while “one” may be prominent, the SANGA which refers to “the entire world,” is affirmed in this way.

§

Moro:

That’s true. Dōgen often uses the term KOKŪ, “space” (Sanskrit: ākāśa).

Shimizu:

The whole of the “mountains and water” is mutually generative with “the individual” (“one”), so this can also be a pivot to say “In a way you are also creating it.” Taking it one step further, this smallest case of the cognizing protagonist and the boat leads to both the idea of “the entire world” and its “transcendental cognizer.” This is sometimes referred to as “former Buddha’s eye” or “the path spontaneously appearing.” A direct affirmation of the world appears in “The ‘mountains and water’ of which I am speaking at the present moment are a manifestation of the words and ways of former Buddhas.”

§

Moro:

Sansuikyō (On the Spiritual Discourses of the Mountains and the Water)*7.

Shimizu:

Yes, Sansuikyō. The mountains and water are composed as a whole, but they do not only subsume everything and Dōgen recognizes that a variety of complex umwelten exist disparately, each of which is a perspective. For example, when looking at “water,” a demon sees it in this way, while dragons and fish see it as a palace, and others may see it as treasure and jewels – he expresses it in many ways. Each one has its own umwelt, its own perspective by which it sees the world, and the world becomes a pivot and in turn, illuminates each one of them. This is what Dōgen says so thoroughly.

His expression itself is a completely logical development from what we’ve examined up to this point. He expresses it as a vision of nature, which I think completely overlaps with perspectivism or what is currently being discussed in anthropology called multinaturalism. Anthropology in the 21st century has started to talk about multinaturalism, which transcends cultural relativism or multiculturalism. If one thinks about it thoroughly, one cannot but see the world in that way.

§

Moro:

Would you say that if it was The Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way which was built up from the bare minimum in a very logical way, then it was Dōgen who suddenly expanded and applied it to nature, umwelten, and the world?

Shimizu:

It was Dōgen, and I think it was Zen which first brought up “the individual” here. “Person” appears in Rinzai Zen: “Upon the lump of red flesh there is a True Man of no Status” and “protagonist.*8” So in a way, it suddenly puts forth the subject of the subject-object pair, and it puts forth objects, and the world, too.

§

Moro:

What I find so amazing about Dōgen is he says things like “people walk, and mountains walk too” nonchalantly. That’s pretty significant, isn’t it?

Shimizu:

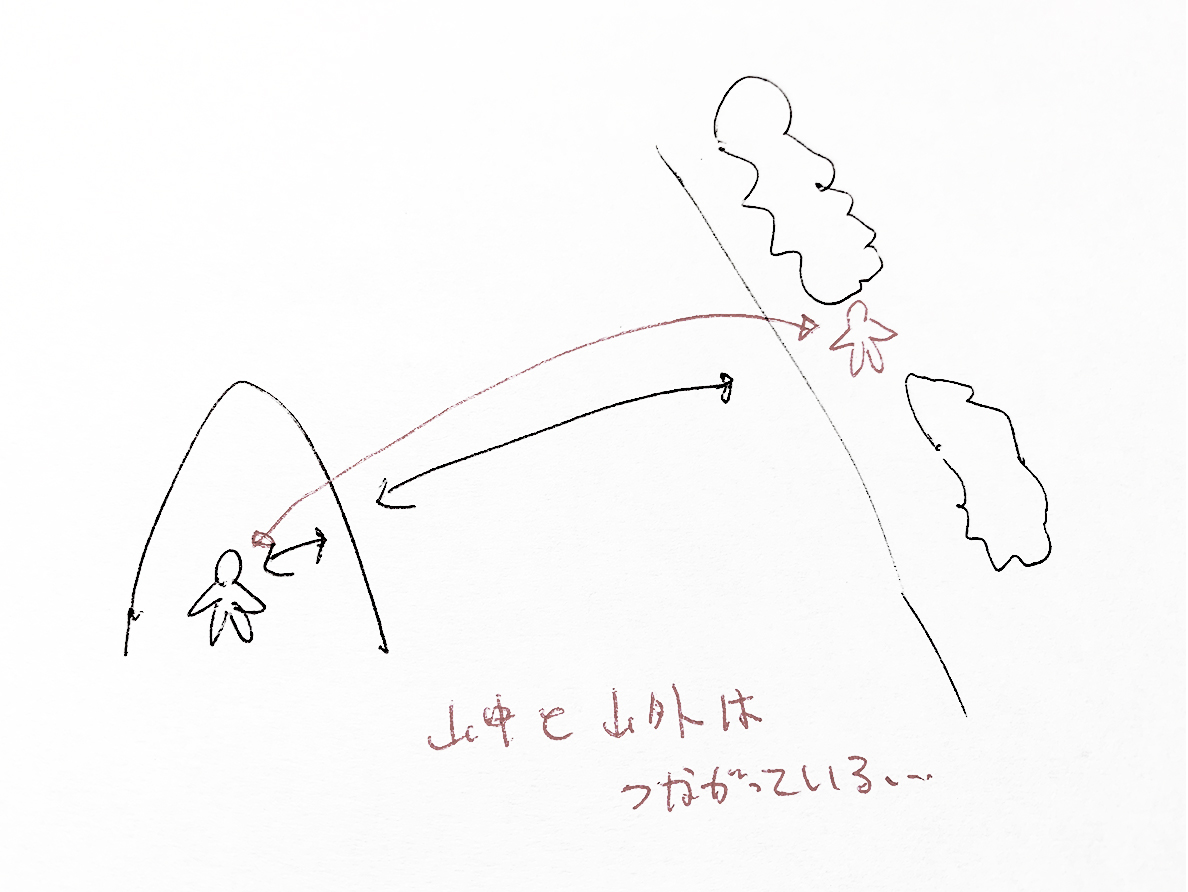

There are people among the mountains. Let’s suppose the boat has become a mountain. If a person is walking among the mountains, at first glance it appears as though there is an actor and an object of the action. But the “mountain” is in fact moving within its relationship with some larger umwelt. The world cannot be established unless we think this way. So the person who is simply within (the mountain) does not understand that, and the person who is simply outside (the larger umwelt) also does not understand. A person looking from a perspective of “I’m outside” has a Simple World Theory. It would be like looking at the 18th-century natural historian Wilhelm von Humboldt from the viewpoint of the anthropologist Keiji Iwata.

If this is the person outside the mountain, and this is the person inside the mountain, then the fact that both of them must not simply be either is what is talked about in SEIZANJŌUNPO, “The verdant mountains are constantly moving on.” If we consider each thing in this way one by one, the next thing to emerge is SEKINYOYASHŌNI, “The Stone Maiden, in the dark of night, gives birth to Her Child.” But what does that mean? A barren woman gives birth to a child at night. Giving birth and being born, but what does “night” mean? When the child is born, the parent becomes a parent. Dōgen is telling us to think about how these two things happen simultaneously.

This is the riddle surrounding the cause or origin and the subsequent event, and how they mutually form each other. I think SEKINYOYASHŌNI probably means to give birth to oneself. The loop of interdependence is more minimal and independent than anything. He’s telling us to look at that first, in the dark. The striking contrast between birth and darkness emerges there simultaneously.

§

Moro:

As I said a moment ago, just as The Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way is understood to transcend language in some ways, I think that Dōgen has been understood to be saying that these things should be experienced physically. That’s why it is very interesting that it is structured as minute and quintessentially philosophical ponderings, and I learned much even as someone who studies Buddhism.

Shimizu:

If you simply read Dōgen without thoroughly thinking about The Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way and Jizang, you probably will wonder what he’s talking about. However, if you put about 60 percent of your effort into investigating Nāgārjuna’s and Jizang’s theories and the other 40 percent into reading Dōgen, you will understand what he is saying. Furthermore, you will feel a connection between the world he speaks about and the worldview of ancient Japanese people and a variety of non-European people. That feeling is very impressive.

§

Moro:

The Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way is very short, including the second chapter we just mentioned, compared to the 75 volumes of Shōbōgenzō. Why does Shōbōgenzō use so many words to so persistently talk about nature, oceans and boats, etc.?

Shimizu:

I think he is purposefully trying to subjectify it using expressions. While saying things like FURYŪMONJI, “wisdom is not imparted through words,” Zen people are grabbing each other by the collars and shouting “Say it! Say it!” at each other. There are even nonsensical exchanges such as “Say the SOSHISEIRAII, ‘Why did Bodhidharma come to China?’, to someone hanging from a tree branch by their teeth.” There must be a moment when something is “said,” when it is expressed and made into a theme. Furthermore, just as “there is no A, so there is no not A,” if we take it as GENMETSUMON, “a return to extinction,” then for the first time a world where “one” is “all” spontaneously appears. This structure appears ubiquitously with Dōgen. The topic of subject-object turns into a discussion of mirrors, does it not?

§

Moro:

Yes, in Kokyō (the Ancient Mirror).

Shimizu:

Kokyō talks about an ancient mirror in which a cognizer can see their mind and eye as objects in the mirror. The fact that they are reflected in the mirror is also a loop of interdependence and mutual generation, or what I think is called the mirror stage in modern French thought. This is another ICHIIMONPA. However, a meta-ICHIIMONPA logic immediately begins to counter this.

That is to say, the Ancient Mirror reflects everything, including both “other” and “I.” If someone else comes along, if a Chinese comes the Chinese is reflected, if a foreigner (from western regions) comes the foreigner is reflected. This is the same as saying that there are many perspectives for “the whole world.” When the question is asked “What do you do when the mirror itself comes along?,” the response is to “shatter it into a hundred pieces,” HYAKUZASSAI. This means that when we think about considering the object world directly, we must approach the issue of “one and many” through meta-ICHIIMONPA.

§

Moro:

The GENMETSUMON approach you mentioned briefly a moment ago.

Shimizu:

To begin with, the twelve links of dependent arising spoken of in early Buddhism is enumerated in statements of the form “there is X, so there is Y”; it starts with ignorance and ends with aging and death, and an explanation of how the world of suffering, duḥkha, is born. This flow is called JUNKAN (the sequential order of observing the twelve links of dependent arising), but it comes as a pair with GYAKUKAN (the reverse order of observing the twelve links) or GENMETSUMON. In other words, if we follow the twelve-fold chain in reverse, such that “there is no Y, so there is no X,” then the world of suffering disappears.

As it happens, the idea of the tetralemma is “neither X nor not X,” which simply avoids saying “this is X.” Therefore, if we carelessly insert a subject in X, then we bring up the whole problem again, which is meaningless. Nāgārjuna negates all such discussions in The Middle Way. The tetralemma can only be used in a narrow subset of propositions. He carefully selects four types in The Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way (HAPPU, “the Eight Negations”).

In contrast, the world of “there is X” is truly varied to begin with. The Sarvāstivāda tried to subjectify each thing in it, but they expanded that world to include everything, and they also tried to transcend the law of excluded middle. That is where the idea of ENGI became lost. However, the GENMETSUMON approach of ENGI is “if A does not exist, B (not A) does not exist,” so based on their subjectification, “(the cause is) neither A, nor not A.” This is because they are making it into an “X exists” statement. Furthermore, because both extremes have established interdependence, this is the final form of tetralemma (the fourth lemma, or proposition).

This is no longer a discussion of why “subject A” exists, but rather an insight into the metalevel structure. Therefore, if we go through the GENMETSUMON approach, the tetralemma can be applied to all “there is X.” The model for the fourth proposition is the same as “neither arising nor ceasing.” If we take as an example “firewood becomes ash,” which we talked about earlier, then each element, firewood or ash, is in a tetralemma-state as it transforms and is destroyed and changes. Of course, life and death can also be thought of in this way: there is a transition from life to death, but even within those there is a minimal before and after, and that change, that transition itself is, in the same vein as the tetralemma, within HŌI.

Dōgen also says in his famous Uji or Being-Time, “The pine tree is time, as is the bamboo.” This is saying that everything is minimally “time.” There is a transition which, moreover, is nested in multiple layers. Dōgen has many mysterious logics. For example, what is Dōgen saying so insistently when he says “One cannot eat a rice cake drawn in a picture?” He is not asking whether the drawn rice cake exists as an object, he is asking how the drawn rice cake was created, what was used to draw it. In other words, it is a stand-in for the question of how an actor creates an object. He thereby says that an object does not simply exist vaguely somewhere outside. This subject “creating” this object world, like the importance of the moment when we express or say something, is an extremely important thing as well.

Keiji Iwata says, “Dōgen wrote Shōbōgenzō as though he were drawing the world in fine detail.” By taking SHINRABANSHOU, “all of creation,” and turning it inside-out to become an expression world, which is in fact the world of the GENMETSUMON approach, Dōgen is saying that the world is indeed neither arising nor ceasing.

§

Moro:

From the standpoint of Buddhism, both Dōgen’s and Nāgārjuna’s theories have Enlightenment and salvation as their goals. During our discussion, I wondered what the aim of your philosophy is.

Buddhism teaches that we should all become enlightened together, but just now you mentioned Dōgen as an expresser. In your philosophy, do you seek to express the world as Dōgen did, or do you have any interest in going in that direction?

Shimizu:

There is some of that, yes. If what the world expresses is “the manifestation of the ways of former Buddhas,” then it is a matter of enlightenment, or how one who has been enlightened looks at the world. I want to unravel the meanings of the diverse expressions of such a world and understand them. In his later years, Kitarō Nishida said, “My philosophy is a creative monadology.” I felt exactly the same way ever since I was young. I did not want to let the close relationships between “one and many” be left as simply a concept. Each person must become the extreme point of creation.

Creation refers to the creation of the world. In some ways, we must be the meaning at the extreme pole of world creation and that, I think, can also be called freedom. If Buddhism gives a sense of freedom and releases us from the constraints of suffering, then that is exactly what creation is.

Conversely, on the side of philosophy, if we shoulder the values of modern thinking as they are, even though we talk of freedom within social systems, at the very least I don’t feel that that is true freedom. Humans must seek out a “more than human” freedom which transcends human freedom. I believe that this is a large task for future civilizations.

§

Moro:

Thank you very much for your talk today. Finally, I’d like to share with the readers a recent book by Takashi Shimizu, published in 2020, Stem Metaphysics: To Be Free From All Dualism*9.